Transformation of the Food System

Today, U.S. farmers produce approximately $143 billion worth of crops and $153 billion worth of livestock each year (USDA, 2013). To produce in such magnitude, and to keep up with market demands, significant changes had to be made to our food system (Dimitri, Effland & Conklin, 2005).

Prior to WWI, almost 40% of the U.S. population lived on farms and their foods were locally grown (Pirog, 2009; Martinez et al., 2010). Consumers would learn about the quality of food through their farmers and most of the foods traveled less than one day to market (Giovannucci, et al., 2010). Americans primarily relied on seasonal foods and few were processed (Martinez et al., 2010). Since then much has changed with the technological advancements in transportation, production and refrigeration. This gave rise to structural changes in the food system. Some of those changes included:

1) the consolidation between producers and processors, which has given control to fewer organizations (Christensen, 2002);

2) the vertical integration of single or partnered organizations where they control various steps along the food supply chain (i.e.: producers own the farms, distribution systems and processing plants);

3) contractual agreements between producers, processors and buyers with an aim in managing farmer and buyer relationships; and

4) the incorporation of new marketing methods, and increase of consumer demands for more diverse shopping options and locations (Jensen, 2010).

These changes have had a big impact upon the food industry, causing many agriculture specialists to conclude that the structure and practices of our current food systems are not sustainable and pose major challenges to our ecological, social and economic health (Hanson & Hendrickson, 2009; Kirschenmann, 2010; Imhoff, 2010; Tagtow & Roberts, 2011).

Food System Challenges

From a triple bottom line perspective, the U.S. food system poses many problems, as it lacks a systems-based approach to the food related issues that cut across ecological, social and economic sectors. Some of these challenges include issues related to pollution, energy, waste and biodiversity (ecological) (Steinfeld et al., 2006; Christensen, 2002; Wood et al., 2005; DeFries et al., 2005); food insecurity, public health, food safety and labor issues (social) (American Public Health Association, 2007; Gilchrist et al., 2007; Straccuzzi & Ward, 2010); and policy, subsides and operational favoritism for high income farmers, loss of financial wealth among local and regional farmers and high costs of hidden externalities (economic) (Imhoff, 2010; Scharff, 2010; Kirschenmann et al., n.d.; Hinrichs, 2003; Foley, Goodman & McElroy, 2012).

These food system challenges seem daunting and overwhelming, but they are not insurmountable. By utilizing a systems-based framework of the whole food system, new knowledge and increased awareness about the many intricately related factors of the system (including the implications it has on ecological, social and economic health), can be addressed (American Public Health Association, 2007); thus, creating a space for more innovative and creative solutions (Nourish, n.d.).

With Americans spending approximately $1.24 trillion on food annually (USDA, 2012), and with the population growing to over 300 million (Pimentel,n.d.), the demand for food is evident. In fact, experts suggest that food demands are growing at a rate of 2% per year (Pimentel, n.d.). The large scale “conventional” food systems have played a significant role in meeting these food needs by increasing production. Still, the challenges related to these food systems and their practices are evident in the literature (Pimbert, 2009; Foley, Goodman & McElroy, 2012; Jensen, 2010; Stevenson & Pirog, 2013). By definition, systems are multi- dimensional, so they should be addressed as such. Affirmatively, local, national and international trends suggest that that is exactly what is transpiring (Tagtow & Roberts, 2011; Hawkes & Ruel, 2011; Russo, 2011; The Food Trust, 2013; Drewnowski, 2005; Berkeley Food Institute, n.d.).

Subsequently, all food systems (larger scale or local and/or regional) directly affect (whether positively or negatively) the availability, diversity, quality, quantity and safety of foods that are necessary for creating and maintaining healthy farms and communities (Tagtow & Roberts, 2011). Thus, with a growing concern for food security, food safety, and the negative impacts upon the environment, interests in a more sustainable food system has increased (Tagtow & Roberts, 2011; Jensen, 2010).

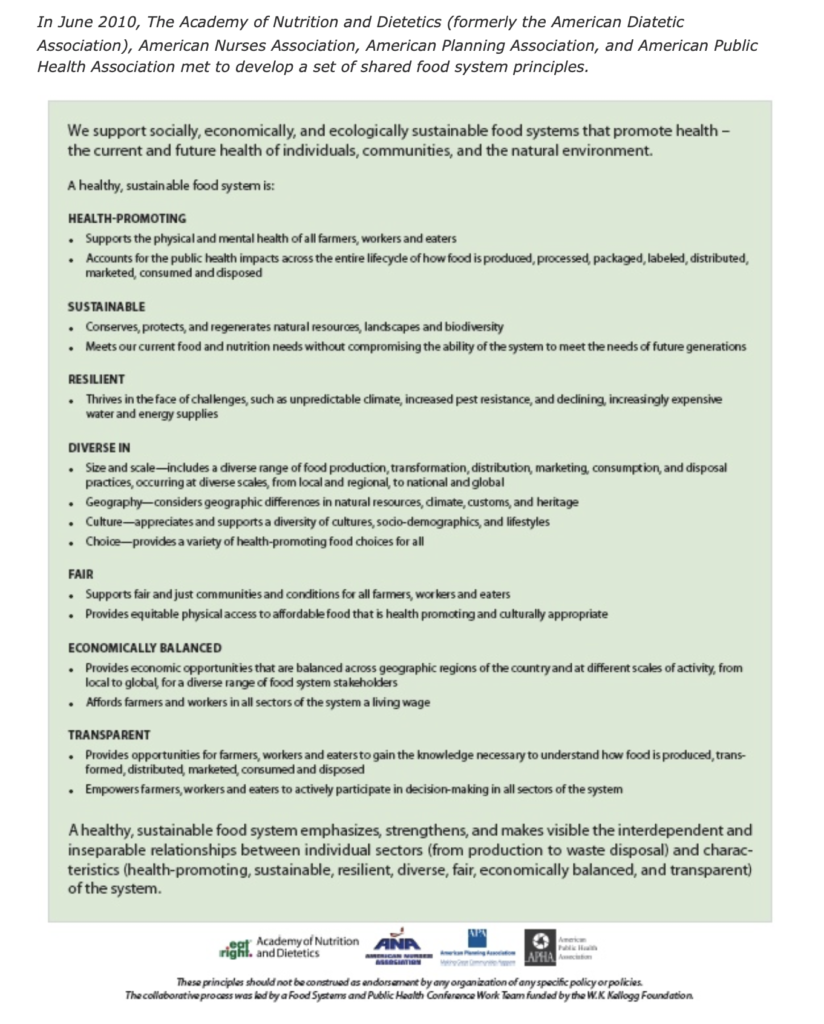

Since the problems within food systems are deeply intertwined and complex, creative solutions that address the ecological, social and economic problems inherent in the current system, need to be developed and implemented. Therefore, in moving toward solutions, a good starting point might be to ensure that all food systems:

“…provide healthy food to meet current food needs while maintaining healthy ecosystems that can also provide food for generations to come with minimal negative impact to the environment. A sustainable food system also encourages local production and distribution infrastructures and makes nutritious food available, accessible, and affordable to all. Further, it is humane and just, protecting farmers and other workers, consumers, and communities”.

American Public Health Association, 2007 – definition of sustainable food systems